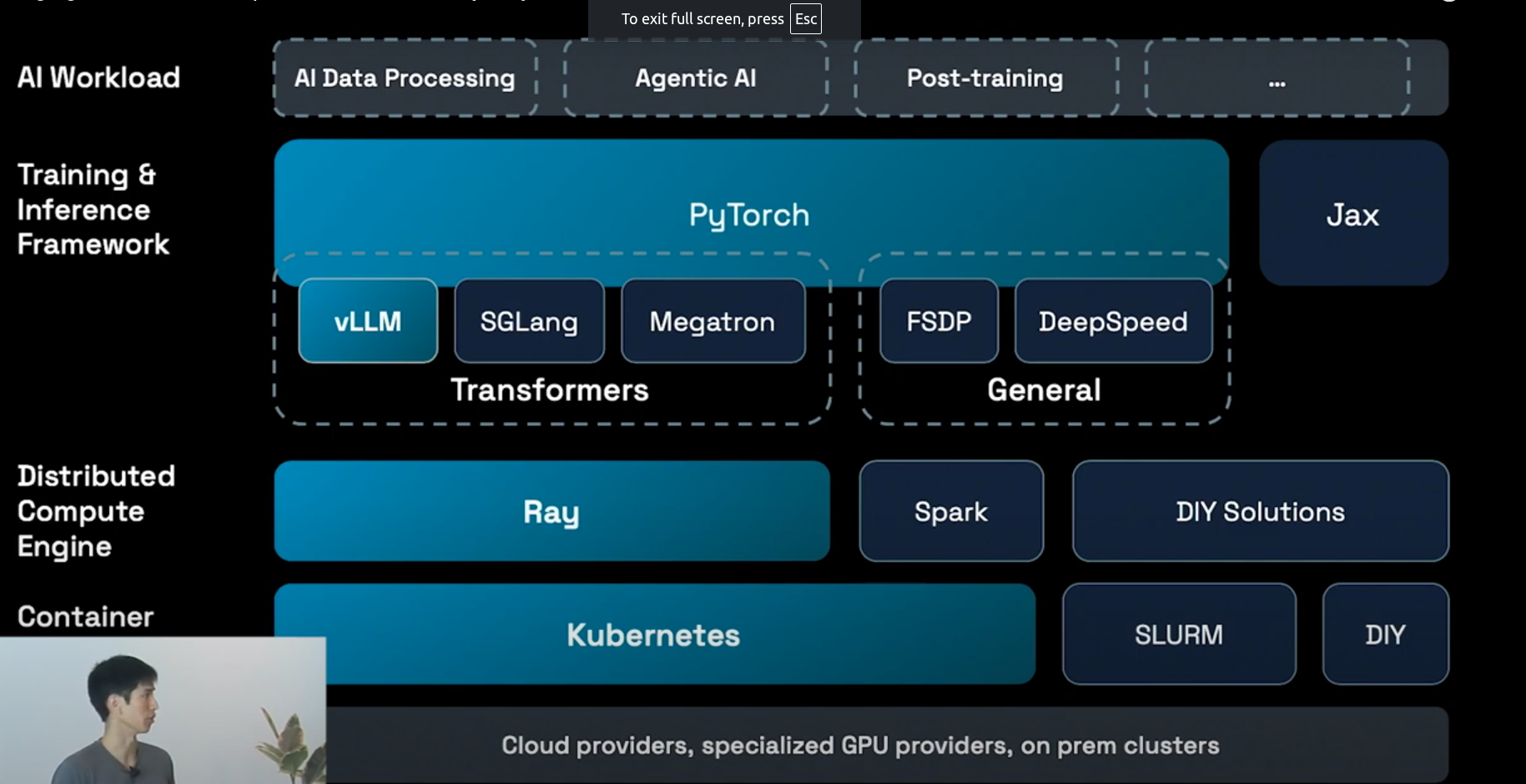

Ray serve

Ray Serve scales each model independently based on its traffic78. This applies across multiple nodes and models7.

When traffic increases, Serve automatically adds replicas of models and can even start new instances to meet demand, scaling up models receiving traffic.

Crucially, Serve does not scale models that are not receiving traffic, preventing wasted GPU resources.

When traffic decreases, Serve automatically downscales models and removes extra nodes, saving GPU resources overnight8. This simple optimization can lead to a 50% cost saving compared to allocating a fixed number of GPUs for peak traffic

Model Layer Optimizations with Ray Serve

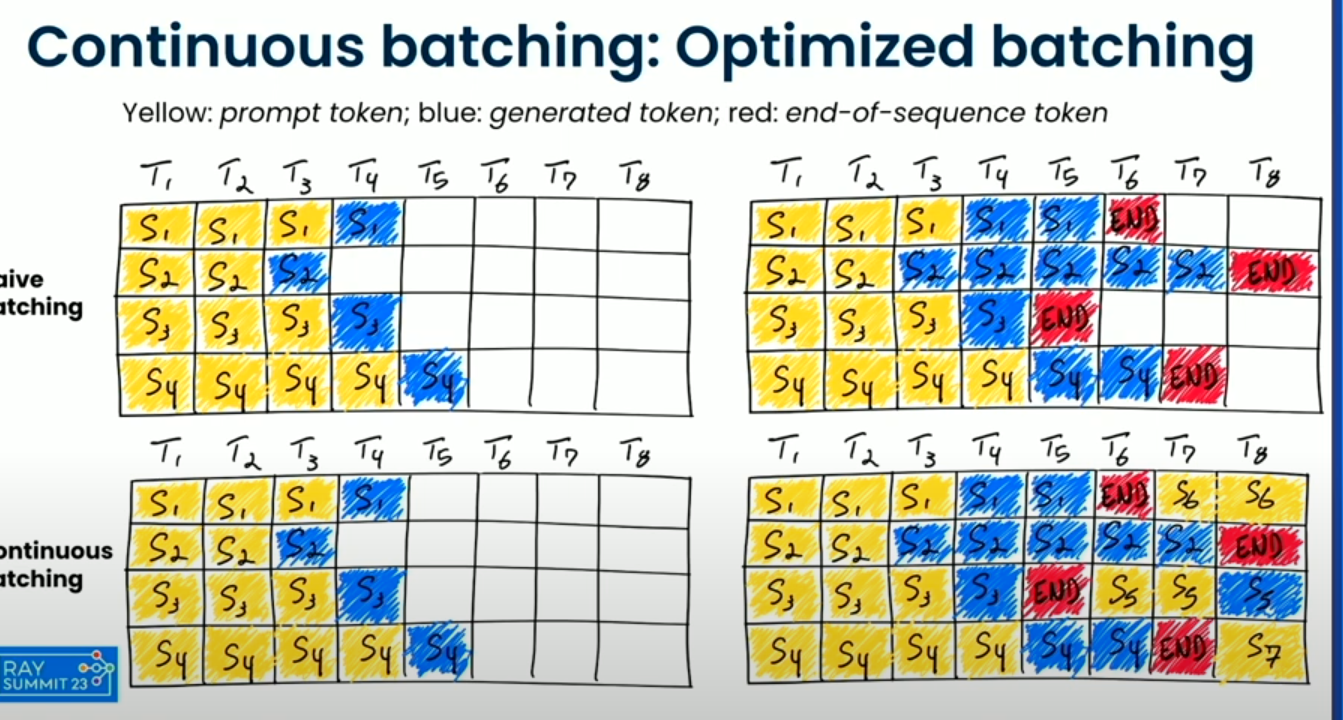

Imagine you have a language model that needs to generate completions for three different prompts. The prompts and their expected token lengths are as follows:

- Prompt 1: “2+2=4” → 10 tokens (s1,s1,S1)

- Prompt 2: “How are neutron stars formed?” → 100 tokens

- Prompt 3: “What is the capital of France?” → 12 tokens

Let’s assume the GPU can handle 2 sequences at a time. Now let’s see how static batching and continuous batching would handle this.

In static batching, you would put all three sequences into one batch. The model starts processing the batch, and it needs to wait for the longest sequence (Prompt 2, with 100 tokens) to finish.

- Prompt 1 (10 tokens) finishes quickly. But the GPU cannot process anything else yet because it’s waiting for the longest sequence.

- Prompt 3 (12 tokens) finishes next, but again, the GPU still waits for Prompt 2 to finish.

- Finally, Prompt 2 (100 tokens) finishes after a long time, and only then can the batch be considered complete.

- Continuous Batching: Instead of waiting for the entire batch to finish, in continuous batching, after each forward pass, the GPU processes one sequence and replaces it with a new sequence that’s waiting to be processed. So, after processing Prompt 1 (which finishes quickly), the GPU immediately starts processing Prompt 3.

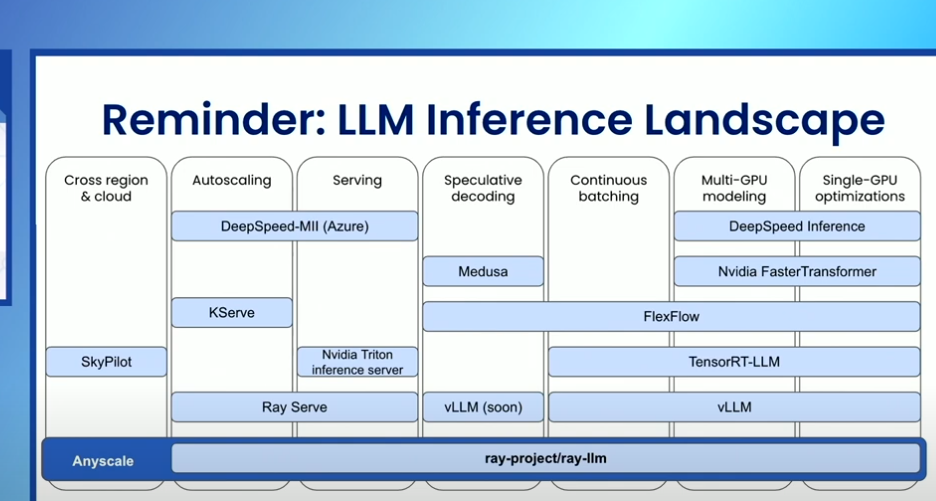

- Ray sever contain all best opensource features in single lib as mentioned in picture

Speculative decoding

Speculative decoding is an optimization technique designed to reduce the time it takes for a language model to generate each token, making it faster and more efficient. The core idea behind speculative decoding is that predicting tokens in a sequence isn’t equally difficult for every token. Some tokens are easier to predict based on the preceding context, while others might require more computational power and time to determine.

To speed up token generation, speculative decoding uses a smaller, faster model (referred to as a “draft” model). For example, a smaller 7-billion parameter model can be up to 10 times faster than a much larger 70-billion parameter model. The smaller model is tasked with predicting a few tokens ahead (let’s say K tokens), which is much faster than waiting for the large model to generate tokens one by one.

Once the smaller model makes predictions, the larger model (which has more capacity and accuracy) steps in to verify the correctness of the predicted tokens. If the smaller model’s predictions are correct, the larger model can immediately accept those tokens and even generate multiple tokens in a single forward pass. This means that the large model doesn’t have to compute every token individually, which reduces the overall time it takes to generate the output.

Note: Eventhough we use Large LLM for verification which is faster then LLM inference

SGLang has implemented this as egale 3 framework

Example

Traditional Speculative Decoding:

- Draft model: Small model (e.g. LLaMA 1B)

- Target model: Full model (e.g. LLaMA 7B/8B)

- The draft model generates k tokens.

- The target model checks if those k tokens are correct.

Eagle 3: Reuse the first few layers of the target model as the draft model

No need to load a separate model Just run:

- Layers 0–N for draft

- Layers N+1–L for verification

This saves memory and reduces latency + I/O overhead.

- A full LLaMA 8B model with 32 layers

- We configure Eagle 3 to use layers 0–7 as the draft

- We’ll decode up to 4 tokens per speculative round

User prompt: "Tell me a joke"

with torch.no_grad():

hidden_state = model.run_layers(input_ids, layer_range=(0, 7)) # Layers 0 to 7

logits = head(hidden_state[-1]) # output of layer 7

draft_tokens = sample_tokens(logits, top_k=20, num_tokens=4)

Now we have 4 speculative tokens:

["Why", "did", "the", "chicken"]

Now we pass the combined input (prompt + draft_tokens) through only layers 8–32:

hidden_state = model.run_layers(

input_ids=concatenate(prompt, draft_tokens),

layer_range=(8, 32),

reuse_cache=True

)

logits = head(hidden_state[-1])

then we check

Are model logits[0] == draft_tokens[0]?

Are model logits[1] == draft_tokens[1]?

┌──────────────────────────────┐

Prompt → │ LLaMA layers 0–7 (Draft pass) │

└────────────┬────────────────┘

│ Sample top-K → draft tokens: ["Why", "did", "the", "chicken"]

↓

┌──────────────────────────────┐

│ LLaMA layers 8–32 (Verify) │ ← prompt + draft tokens

└────────────┬────────────────┘

↓

Check if target logits match draft

✔ If match → accept

✘ If mismatch → reject and resume

Rayllm build VLLM

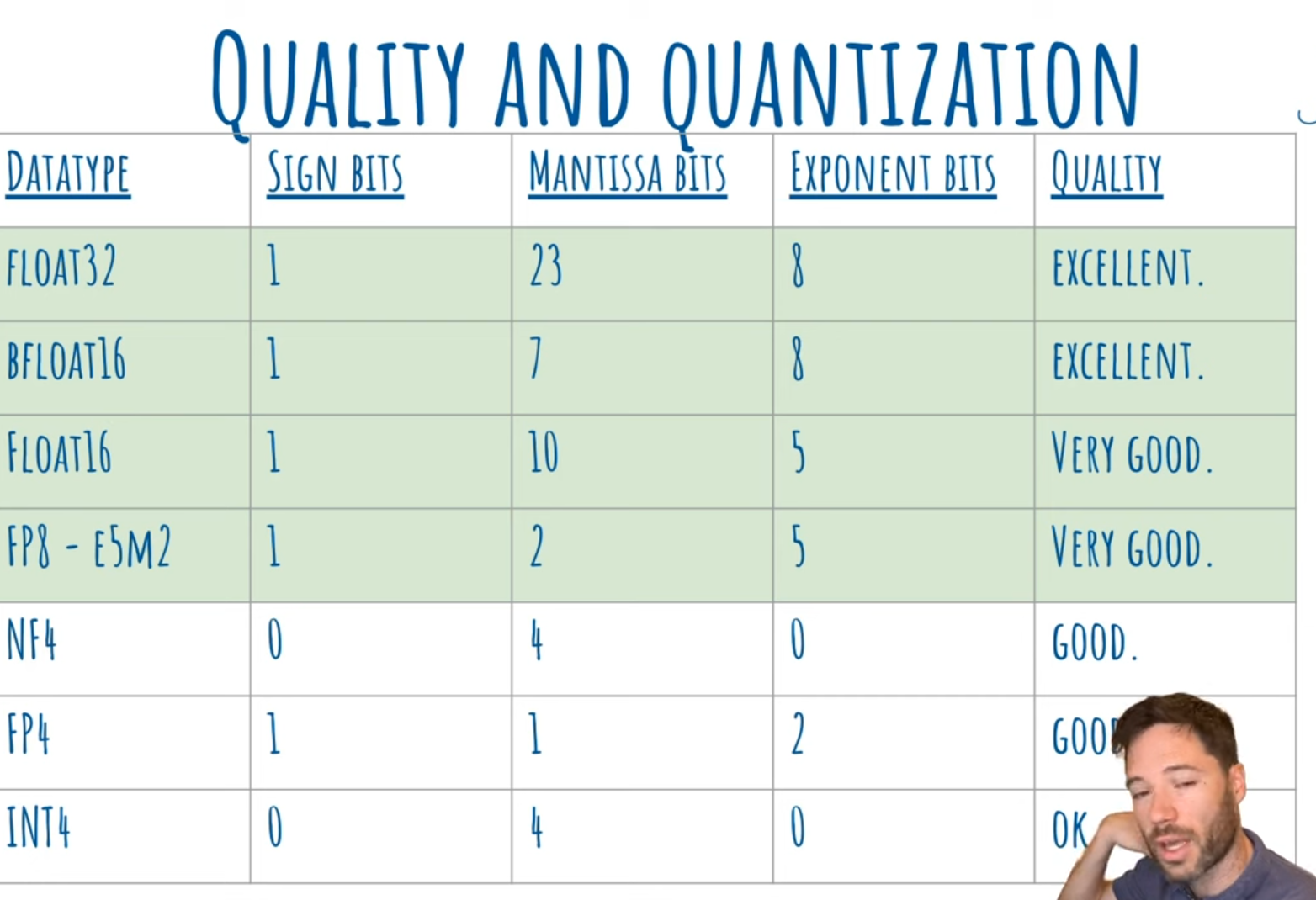

- Floating point allows us to represent very large and very small numbers with a compact number of bits.

- The number is split into:

- Sign bit → whether it’s + or -

- Exponent bits → how big or small (the “scale”)

- Mantissa bits (or significand) → the actual significant digits

Float = Sign × Mantissa × 2^(Exponent)

Why integer?

- Integer quantization (like INT4) is simpler → no exponent → fixed range → more compact → but less flexible for values that vary a lot in scale.

| Datatype | Sign Bits | Mantissa Bits | Exponent Bits | Dynamic Range | Precision | Typical Use | Quality |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Float32 (FP32) | 1 | 23 | 8 | Very wide | Very high | Training | Excellent |

| BFloat16 (BF16) | 1 | 7 | 8 | Same as FP32 | Medium | Training (TPUs, GPUs) | Excellent |

| Float16 (FP16) | 1 | 10 | 5 | Smaller than FP32 | Good | Mixed precision training & inference | Very good |

| FP8 (E5M2) | 1 | 2 | 5 | Same range as FP16 | Low | Inference (Hopper, Blackwell) | Very good |

| NF4 (Normal Float 4) | 0 | 4 | 0 | None (fixed scale) | Good | Quantized inference | Good |

| FP4 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Small | Very low | Research-stage inference | Good (suspected) |

| INT4 | 0 | 4 | 0 | None | Very low | Final quantized inference | OK |

- GPU that support different floating points operation per sec

Inference Optimization

KV caching

Before a language model like GPT can understand or generate text, raw input text must be transformed into a format it understands tokens.

Tokenization

When we give GPT a sentence like:

text = "The quick brown fox"

inputs = tokenizer(text, return_tensors="pt")The tokenizer:

- Breaks the sentence into subword units (tokens).

- Maps them to integers using a pre-trained vocabulary (e.g., 50,257 entries in GPT-2).

- Returns:

{

'input_ids': tensor([[464, 2068, 1212, 4417]]),

'attention_mask': tensor([[1, 1, 1, 1]])

}Each token ID (like 464) corresponds to a word or part of a word.

What Happens Inside the Model

Once the input is tokenized, it’s passed to the model:

outputs = model(**inputs)

logits = outputs.logitsThe output will have 50257 vocablity and each token with there attention score

| Text | vocab1 | vocab1 |

|---|---|---|

| input text1 | 10.39 | 10.9 |

| input text 2 | 10.31 | 9.8 |

Output of the Model

logitsshape:(batch_size, seq_len, vocab_size)- Each position contains a vector of size equal to the vocabulary size.

- These are unnormalized scores for predicting the next token.

Example:

logits.shape = torch.Size([1, 4, 50257])Here:

- 1 = batch size

- 4 = sequence length

- 50257 = number of possible tokens

You can get the most probable next token using:

last_logits = logits[0, -1, :]

next_token_id = last_logits.argmax()Vocabulary Explained

The model has a fixed vocabulary (e.g., 50,257 tokens in GPT-2), learned during training.

- Tokens can represent words, subwords, punctuation, or whitespace.

- The model only generates tokens from this fixed vocabulary.

- It cannot invent new words or characters only sequences of known tokens.

tokenizer.decode(464) ➝ 'The'

tokenizer.decode(next_token_id) ➝ ' lazy'Manual Token Generation: One-by-One

You can simulate generation manually:

for _ in range(10):

next_token_id = generate_token(inputs)

inputs = update_inputs(inputs, next_token_id)

generated_tokens.append(tokenizer.decode(next_token_id))This is auto-regressive generation each new token depends on the full previous sequence.

Why It’s Slow Without Caching

Each time we generate a new token:

- We re-feed the entire input sequence to the model.

- Attention layers recompute everything from scratch.

- This becomes increasingly expensive as the input grows.

Key-Value Caching (KV Caching)

Each transformer attention layer internally computes:

- Keys (K) and Values (V) for every token.

These are used to compute attention over the sequence:

Attention(Q, K, V) = softmax(QKᵀ / √d) * VThe trick: once we’ve computed K and V for earlier tokens, we don’t need to recompute them.

Example with KV-Caching

# First step

next_token_id, past_key_values = generate_token_with_past(inputs)

# Following steps

inputs = {

"input_ids": next_token_id.reshape(1, 1),

"attention_mask": updated_mask,

"past_key_values": past_key_values

}Now the model only computes attention for the new token — the old tokens are already cached.

Input Batching

Batching means feeding multiple input sequences to the model at the same time instead of one-by-one.

we have multiple prompts:

prompts = [

"The quick brown fox jumped over the",

"The rain in Spain falls",

"What comes up must",

]

We tokenize them together:

inputs = tokenizer(prompts, padding=True, return_tensors="pt")This returns a tensor of shape [batch_size, seq_len], where:

Each row is a tokenized prompt.

All rows are padded to match the longest prompt.

input_ids:

tensor([[ 464, 2068, 1212, 4417, 716, 262],

[ 464, 1619, 287, 743, 5792, 0],

[ 1332, 1110, 389, 5016, 0, 0]])In transformers, each token is aware of its position in the sequence using position_ids.

With padding, we must offset position IDs so they begin at 0 after the padding:

position_ids = attention_mask.cumsum(-1) - 1

position_ids.masked_fill_(attention_mask == 0, 1)

Continuous batching.

Refere above Continuous Batching from Ray serve

Dynamo

A Datacenter Scale Distributed Inference Serving Framework

TensorRT-LLM

TensorRT-LLM provides users with an easy-to-use Python API to define Large Language Models (LLMs) and support state-of-the-art optimizations to perform inference efficiently on NVIDIA GPUs. TensorRT-LLM also contains components to create Python and C++ runtimes that orchestrate the inference execution in performant way.

ZML

ZML simplifies model serving,

ensuring peak performance and maintainability in production.

VLLM

Resources

- LLM Inference Handbook

- Mastering LLM Techniques: Inference Optimization

- https://www.bentoml.com/blog/the-shift-to-distributed-llm-inference

- Mastering LLM Inference Optimization From Theory to Cost Effective Deployment: Mark Moyo

- The AI Engineer’s Guide to Inference Engines and Frameworks

- Inside vLLM: Anatomy of a High-Throughput LLM Inference System

- Fast LLM Inference From Scratch

- https://multimodalai.substack.com/p/the-ai-engineers-guide-to-inference

- https://lilianweng.github.io/posts/2023-01-10-inference-optimization/

- The AI Engineer’s Guide to Inference Engines and Frameworks

- https://multimodalai.substack.com/p/understanding-llm-inference